Water and politics in Kenya

From 5 to 26 May, I was in Kenya for the start of a new phase of fieldwork in the context of the research project Water sector reforms and interventions in urban Kenya. The impact on the livelihood of the poor, a project that is carried out in very close collaboration with Sam Owuor (University of Nairobi). Kenya’s water sector reforms are laid down in the Water Act 2002. Under the Act, autonomous water and sanitation (or sewerage) companies – so-called WASCOs – are given the responsibility to provide water and sanitation services within urban areas. The WASCOs are expected to be managed on commercial principles. Yet, the key word is not ‘privatisation’ but ‘commercialisation’: water is considered by the Kenyan government as both a social and an economic good, to be available for all Kenyans and at a price reflecting its market value (cost recovery). The government also recognises that the poor cannot afford to pay such prices, a problem that has to be solved by subsidised rates. This is the overall goal of the National Water Resources Management Strategy (NWRMS – 2006-2008), namely “to eradicate poverty through the provision of potable water for human consumption and water for productive use”.

![One of the operational water kiosks in Kisii, with privatewater vendors in the background [photo: Dick Foeken] One of the operational water kiosks in Kisii, with private water vendors in the background [photo: Dick Foeken]](/sites/default/files/pictures/General%20ASC%20info%20pages/Dick1.jpg) The research project particularly focuses on two towns in the western part of Kenya: Homa Bay and Kisii. This is no coincidence, because besides the implementation of the new water companies, both towns have also been involved in a major water intervention programme called the Lake Victoria Water and Sanitation Initiative (in short LVWATSAN, implemented by UN-Habitat and co-funded by the Dutch government), implying renovation and extension of the existing water infrastructure, the construction of extra capacity as well as so-called water kiosks in the low-income areas. Especially the latter – the water kiosks – are supposed to benefit the poor by giving them access to safe and affordable water. However, while in both Homa Bay and Kisii, all water kiosks should have been operational since about 2008, reality is different. In Homa Bay, only two (out of 12) have been operational; and only now and then. All others have been faced with “some issues”; and when you ask What “issues”?, it is said that there are (or were) “technical” or “organisational” problems. In most cases, there is ‘politics’ behind it, because, as with everything in Kenya, water IS politics. For that reason, besides the livelihood aspect of the water interventions, the ‘political economy’ of the water supply in the two towns is the second major leg of the project. In general, the situation in Kisii is better than in Homa Bay: out of a total of 12 kiosks, 8 appeared to be operational, though most of them ‘irregular’ – again, usually because of “some issues”.

The research project particularly focuses on two towns in the western part of Kenya: Homa Bay and Kisii. This is no coincidence, because besides the implementation of the new water companies, both towns have also been involved in a major water intervention programme called the Lake Victoria Water and Sanitation Initiative (in short LVWATSAN, implemented by UN-Habitat and co-funded by the Dutch government), implying renovation and extension of the existing water infrastructure, the construction of extra capacity as well as so-called water kiosks in the low-income areas. Especially the latter – the water kiosks – are supposed to benefit the poor by giving them access to safe and affordable water. However, while in both Homa Bay and Kisii, all water kiosks should have been operational since about 2008, reality is different. In Homa Bay, only two (out of 12) have been operational; and only now and then. All others have been faced with “some issues”; and when you ask What “issues”?, it is said that there are (or were) “technical” or “organisational” problems. In most cases, there is ‘politics’ behind it, because, as with everything in Kenya, water IS politics. For that reason, besides the livelihood aspect of the water interventions, the ‘political economy’ of the water supply in the two towns is the second major leg of the project. In general, the situation in Kisii is better than in Homa Bay: out of a total of 12 kiosks, 8 appeared to be operational, though most of them ‘irregular’ – again, usually because of “some issues”.

![The 12 assistants and the 3 supervisors [photo: Dick Foeken]. The 12 assistants and the 3 supervisors [photo: Dick Foeken]](/sites/default/files/pictures/General%20ASC%20info%20pages/Dick2.jpg) The new fieldwork concerned a survey in Kisii among some 200 households in four different low-income neighbourhoods where a water kiosk had been put up. Three of these have been operational for several years, though mostly on-and-off. The fourth one is put up in an area where people face great problems regarding water in the dry season, but so far the kiosk has not yet been operational (so we hope to be able to ‘measure’ the people’s expectations regarding this one and compare that with ‘ reality’ in the other three areas). A detailed questionnaire had been developed (which had also been used in Homa Bay, two years ago). The main part of the preparative work we had to do concerned the selection and training of field assistants. We started with 24 and after three days of training we remained with 12. It was interesting to see how, in three days time, this group developed from a loose collection of individuals to a quite close group, ready “to do the job”. The actual survey was supervised by Romborah Simiyu, my PhD student from Moi University (by the time of writing this text, the survey was still going on) and well-known at the ASC.

The new fieldwork concerned a survey in Kisii among some 200 households in four different low-income neighbourhoods where a water kiosk had been put up. Three of these have been operational for several years, though mostly on-and-off. The fourth one is put up in an area where people face great problems regarding water in the dry season, but so far the kiosk has not yet been operational (so we hope to be able to ‘measure’ the people’s expectations regarding this one and compare that with ‘ reality’ in the other three areas). A detailed questionnaire had been developed (which had also been used in Homa Bay, two years ago). The main part of the preparative work we had to do concerned the selection and training of field assistants. We started with 24 and after three days of training we remained with 12. It was interesting to see how, in three days time, this group developed from a loose collection of individuals to a quite close group, ready “to do the job”. The actual survey was supervised by Romborah Simiyu, my PhD student from Moi University (by the time of writing this text, the survey was still going on) and well-known at the ASC.

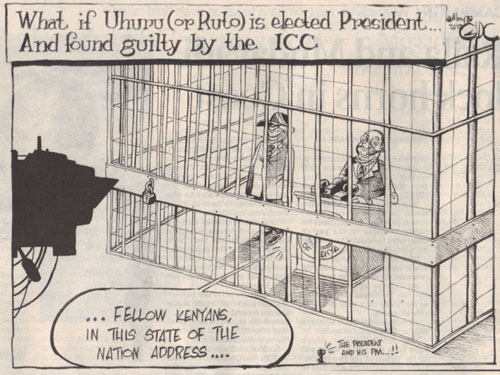

Meanwhile, in Kenya, the major headlines in the newspapers concerned – of course – politics, especially the next presidential elections (even though they will probably not be held before March 2013). New alliances are forged, the most important one between the two former enemies Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto. Both are “presidential hopefuls”, running for the highest office in the country. In order to prevent that Raila Odingo will become the next president (as he will almost certainly win the first round), this alliance is meant to support the number two in the second round. But Uhuru and Ruto have something else in common as well: they both will be tried by the International Criminal Court in The Hague because of their assumed role in the post-election violence in 2008 (they are part of what in Kenya is called the “Ocampo Four”). The astonishing thing is that both candidates seem not to mind this at all in their quest for the presidency, despite for instance very critical articles in the newspapers. A heading like “Why risk national catastrophe for the Ocampo Four?” (Sunday Nation, 20 May 2012) is all too clear about it. And in the same newspaper, in his unparalleled way, Gado ‑ the Nation’s famous cartoonist ‑ shows how this ‘catastrophe’ could look like:

Dick Foeken, 7 June 2012