Africa’s youth and conflicts: a Sub-Saharan spring?

Mirjam de Bruijn is Professor of Citizenship and Identities in Africa at Leiden University. She is an anthropologist whose work has a clearly interdisciplinary character, with a preference for contemporary history and cultural studies. She focuses on the interrelationship between agency, marginality, mobility, communication and technology, specializing in West and Central Africa.

Recent travels to Chad, Cameroon and Mali confronted me with the conflicts in these countries as well as in the Central African Republic, and the youth’s involvement in them. How are we as researchers to analyse the conflicts and protests, what questions and fields of study should we explore? Are we observing a Sub-Saharan spring?

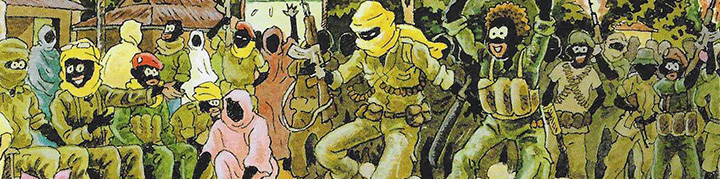

Opposed youth groups in CAR

In Cameroon I worked on a project with researchers from CAR. Since 2013 CAR has entered a new cycle of violence. Seleka and anti-Balaka are opposed groups of mainly youth who fight in a rhythm of vengeance. The government controls the capital city Bangui, but other parts of the country are under control of the diverse ‘rebel’ groups. Both sides are mainly filled with young (wo)men.

Salaries cut in Chad

In Chad I met young men who had just been released from prison where they had been tortured on accusation of disturbing the order. Since January this year Chad has entered a new period of protests and strikes. It was not acceptable for most people that salaries were cut by half and indemnities were not paid. Families could no longer pay for the school fees of their children and some families could only afford one meal a day. It was another period of scarcity in a long sequence of protests in, what is in fact, bankrupt Chad since November 2015. Youth are raising their fists against the regime, but they have little power as the oppression is far more powerful. Since a month now the internet has been cut down again. (This research done in Chad from 2014 to now about youth movements/hardship gives more insight.)

Protests in Anglophone Cameroon

In Cameroon I stayed in Buea, the Anglophone part of the country. In June 2016 Anglophone lawyers started a strike (read the story of this Cameroonian lawyer), followed by teachers, to fight against their experience of inequality and marginality. The repressive answer of the regime led to a deepening of the crisis and a revival of the cry for independence/separation that is a recurrent theme since independence. The secession movement, as it is called, grew and has its ramifications in the diaspora. Today large parts of Anglophone Cameroon are controlled by groups of armed youth. Youth are arrested, houses and whole villages burnt by the police and military forces.

Uprisings in Mali

In Mali I was confronted with the situation in Central Mali where many youth are armed, organized in scattered groups under the banner of Jihad, or, as others claim, under ethnic banners. A specific group of nomads is particularly involved. They claim their marginal position as incentive for their strife. The response to increasing resistance and violence in Mali is the military approach supported by the international community in the form of the UN-mission, G5 Sahel and the French operation Barkhane. In the capital city Bamako youth regularly protest against the situation and call for peace (read for instance this or this article).

Using the right words

The situation is overwhelming and I wonder how to research and report about these situations. Currently, I follow individuals and their actions, both on the ground and in social media, and try to make sense of what is happening. When, at the European Social Science History conference in Belfast, I was listening to researchers-historians who work with the biography-method to unveil situations of deep violence in the past (like the holocaust(s), Gulag, etc.), I wondered if one can say that we are observing such situations in Africa today - interpreting and researching today’s violence and conflicts is a tricky affair. Maybe our sentiments will take us along, and we can easily use wrong words to depict the situation. We will not be the first researchers to make such mistakes.

I take here the risk to be too simple and relate the developments I observe to two important changes in the environment of the youth: 1. The increase in access to new information and communication technologies, and 2. the subsequent effect of a youth that is more informed about the world and its (history of) inequality.

The role of ICTs

One of the questions I posed myself the past decade in my research is: what is the role of ICTs in these new political developments, especially of mobile phones and smart phones? One of the effects of new forms of communication is the organization of youth movements or rebel groups, who use phone calls, sms, whatsapp, to organize their actions (see Branch & Mampilli 2015). We observe a new form of movements that pop-up any moment and then easily disperse; hybrid movements (Alex de Waal & Ibreck). The movements in Mali, Cameroon, Chad and CAR seem to answer to this pattern. The governments regularly cut down the internet.

(Dis)information

Another effect of these ICTs is the growing flow of (dis)information. Young people for instance, unite in whatsapp groups; that is their platform to exchange and share information. The spread of documents, photos, films and audio messages in this parallel socio-political space, is enormous. The huge whatsapp groups of diaspora and on-the-ground Cameroonians to report about the atrocities of the government is an example. And in Central Mali preaches of the almost mythic Muslim leader Hamma Koufa, with his messages about Jihad, tell the youth how to behave.

Whose legitimacy?

What these ‘forgotten youth’ ask for is legitimate from their point of view: they want access to all they need to carve out a decent life in a modern world. They are fed up with the corruption and the inequality. So, what some see as belligerent youth, others consider youth movements that claim their rights. What for some is an illegal act, it is not for others (De Bruijn & Both 2017). The claim of the youth in these four countries is not complicated: they want a better future.

Products of colonial histories?

Can we summarise the causes of these conflicts as ‘identity dynamics and search for citizenship’? And can we see the youth’s identity dynamics and search for citizenship as an answer to the continuation of colonial and post-colonial constraints and imperial dispositions in the present, as Stoler suggests in her book Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times (2016)? I recently concluded in a text I wrote with Jonna Both (forthcoming in 2018): ‘(…). In the regions of our research, more recent conflicts, repressions, and political regimes can indeed be seen as connected to (or even products of) colonial histories, although they also come with their own duress.’

The post-colony in Mali, Cameroon, CAR and Chad has turned out to be a confrontation between different generations, informed by ICTs, accompanied by multiple forms of violence, and with no other way out for the ‘forgotten youth’ than to protest. Whether we are observing a Sub-Saharan spring will only be learned from the future.

References

Branch, Adam and Zachariah Mampilly, (2015) Africa Uprising, popular protest and political change, African Arguments, London: ZED Books

De Bruijn, Mirjam & Jonna Both (2017) Youth Between State and Rebel (Dis) Orders: Contesting Legitimacy from Below in Sub-Sahara Africa. In: Small Wars & Insurgencies, vol. 28 no. 4-5, p. 779-798

De Bruijn, Mirjam & Jonna Both (2018, forthcoming) Realities of Duress, in: Conflict and Society

Top illustration: detail from a book page of Tempête sur Bangui (2015), by Didier Kassai.

Lower photo: Boukary Sangaré.

This post has been written for the ASCL Africanist Blog. Would you like to stay updated on new blog posts? Subscribe here! Would you like to comment? Please do! The ASCL reserves the right to edit, shorten or reject submitted comments.

Add new comment