Exploring Ancient Nubia

Countless sites in the desert of northern Sudan and southern Egypt hold the remains of millennia-old temples, towns and tombs of ancient Nubia, one of the great civilizations of the ancient world. Yet, ancient Nubia is still largely a mystery. In the early twentieth century, archaeological excavation in the area was spurred on by dam construction at Aswan, which was going to drown ancient Nubian lands. Stunning objects, in terms of both skills and creativity, were unearthed, and in many cases shipped off abroad, under the availing ‘fifty-fifty split’ law (half of the objects for the expedition, half for the country). The Boston Museum of Fine Arts now houses the second largest collection of ancient Nubian archaeological artefacts in the world. In recent years, unfortunately, a lack of funds has meant it has been stacked away in depot.

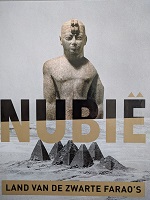

Exhibition in the Netherlands

End of 2018, however, more than 300 objects from the Boston collection travelled to the Netherlands where they are on display in the Drents Museum in Assen until 5 May 2019. A recent publication by the Boston museum, Arts of Ancient Nubia, and a Dutch-language catalogue, Nubië – land van de zwarte farao’s (Nubia – land of the black pharaohs), accompany the exhibition. Part of the text in the Dutch volume is based on the Boston publication; both works are beautifully – and differently – illustrated. Both books can be borowed from the ASCL Library.

One of the eye-catchers in the Assen exhibition is a burial bed from around 2000 BC (the Classic Kerma Period). The bed is partly a modern reproduction, but not its wooden legs in the shape of cattle legs, with hooves, tendons and bones carved with extraordinary anatomic precision. Such legs of royal burial beds were plated with gold. The footboard of the bed is decorated with three rows of ivory inlays. Many such inlays have been found in Nubia, depicting geometric shapes and plants, as well as animals that must have been around at the time such as lions, hyenas and elephants, and imaginary creatures such as flying giraffes.

Publications

Arts of Ancient Nubia and Nubië – land van de zwarte farao’s paint a picture of Nubia’s powerful past. Nubia and Egypt were major rivals, alternatively conquering each other. The Nubians were in close contact with neighbours from central Africa to the Red Sea and the Mediterranean, incorporating Egyptian and other foreign elements in their art, architecture and engineering. A beautiful gilded silver amulet from the Napatan period shows Nubian queen Nefrukekashta being nursed by the Egyptian goddess Hathor. While Hathor is tall and slender, in the way the Egyptians preferred, Nefrukekashta is heavier and more voluptuous, reflecting the Nubian ideal.

Both volumes devote a chapter to the Nubian expeditions between 1913 and 1932, led by the American Egyptologist George Reisner, to whom the Boston museum owes its Nubian collection. A meticulous excavator and recorder, Reisner laid the foundation for subsequent scientific archaeological work in the region. At the same time, he was blind to the Nubian treasures being actually Nubian, that is, the work of a black African people. His racist worldview, commonplace among scientists of his time, made him regard, unquestioningly and without evidence, any work of art and skill as Egyptian import or the produce of Egyptian immigrants.

Heritage of a black African people

This racist perspective, briefly mentioned in the introductory chapter of the Dutch catalogue, has long stood in the way of a full appreciation of Nubia as one of the great ancient civilizations of the world. In fact, not until the sixties and seventies of the last century, when construction of the second Aswan dam gave the impulse to a second wave of Nubian “salvage archaeology”, did it start to dawn upon some in Western science that the Nubian heritage was truly Nubian. Contemporary archaeology is not just concerned with safeguarding precious finds, but wants to piece together the life, history and beliefs of people in ancient times. Sudanese archaeologists, in particular, may offer new perspectives, just as contemporary Nubians, whose stories recount the ancient past, and in whose material culture and languages similarities have been recognized.

Dams and sand

Dams and sand

Nubian archaeology needs the time and funds still to explore vast territories of arid land. But continuing plans for dam building in the Nile threaten this. In addition, looting is a serious problem, as are the harsh desert winds from which some of the sites increasingly suffer, including the pyramids at Meroe, a UNESCO World Heritage site. For Nubian archaeology it is a race against the clock.

Additional sources used:

- Amy Maxmen’s podcast (2018) Finding Nubia

- Maria Costa De Simone’s dissertation at the University of Leiden (2014) Nubia and Nubians the 'museumization' of a culture.

Helpful terms for a search in the African Studies Centre Library section within the catalogue of the Leiden University library are Nubian polity and Kush polity.

Heleen Smits