Germanin: Nazi perspectives on an aspect of Central African colonial history

At the height of World War II the German-language feature film Germanin: die Geschichte einer kolonialen Tat (Germanin: the story of a colonial deed) was released in 1943. The film was based on a novel of the same name written by Dr. Hellmuth Unger. Unger was a medical practitioner and fervent supporter of the National Socialist Regime in Germany. From May 1933 onwards Unger was active in the NSDAP, in particular in the field of “Bevölkerungspolitik und Rassenpflege”. The film Germanin depicts the fictional exploits of a professor Dr. Achenbach who leads an expedition to Central Africa, Northern Rhodesia (contemporary Zambia) and Belgian Congo (contemporary Congo DRC) in order to test Germanin, a new drug to treat Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), or sleeping sickness. The film is National Socialist propaganda, packaged as an entertaining adventure, with an exotic representation of Africa and African populations as its backdrop.

At the height of World War II the German-language feature film Germanin: die Geschichte einer kolonialen Tat (Germanin: the story of a colonial deed) was released in 1943. The film was based on a novel of the same name written by Dr. Hellmuth Unger. Unger was a medical practitioner and fervent supporter of the National Socialist Regime in Germany. From May 1933 onwards Unger was active in the NSDAP, in particular in the field of “Bevölkerungspolitik und Rassenpflege”. The film Germanin depicts the fictional exploits of a professor Dr. Achenbach who leads an expedition to Central Africa, Northern Rhodesia (contemporary Zambia) and Belgian Congo (contemporary Congo DRC) in order to test Germanin, a new drug to treat Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), or sleeping sickness. The film is National Socialist propaganda, packaged as an entertaining adventure, with an exotic representation of Africa and African populations as its backdrop.

Germanin : drug discovery and development

Germanin : drug discovery and development

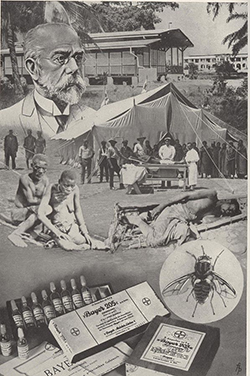

In the early 20th century, a series of epidemics across equatorial Africa brought tropical medicine to the top of the European colonial agenda and raised awareness of the threat of infectious diseases, such as the African sleeping sickness (African Trypanosomiasis, HAT). This disease posed a threat not only to Europeans travelling to the colonies but also to the local population, as well as to the economic value of the colonies themselves. In fact, the problem was so great and so worrying that from 1901 to 1913 the colonial administrations sent a total of fifteen special research missions to Africa to study the disease. The breakthrough came in 1916 when a group of scientists from the German pharmaceutical company Bayer discovered a substance which was based on dye. The drug was called Bayer 205 and showed outstanding therapeutic effects. As Germany had already lost its colonies, the Bayer company, supported by the German government, negotiated with the English and Belgian governments and was allowed to send an expedition to Africa. During 1921 and 1923 the new drug was tested in English Rhodesia and Belgian Congo and proved exceptionally successful. In due course, the drug Bayer 205 was named Germanin and it was subsequently proposed to use it for political leverage: knowledge and use of the new drug was to be given only in exchange for a partial return of the former German colonies. However, the reactions of the international media quickly put an end to these plans even before the proposal had reached governmental level. In the end, French pharmacist Ernest Fourneau elucidated and published the structure of Bayer 205 in 1924.

Germanin : the film

Content

The renowned German professor Dr. Achenbach is desperately searching for a serum in Africa to combat sleeping sickness. A breakthrough is imminent, when the professor learns that the First World War has broken out in Europe and that the English have also declared war on the Germans in Africa. Achenbach's laboratory is destroyed by British soldiers and he is forced to continue his investigations in Germany.

After the discovery of an effective drug for the treatment of African sleeping sickness at Bayer Laboratories, Achenbach returns to Africa where the drug is most urgently needed. However, the British colonial authorities do everything they can do in their power to hamper Achenbach’s mission and work.

Production and release

Production and release

Germanin was shot in Italy and at the Babelsberg Ufa studios in Potsdam in 1942. It was directed by Max Kimmich, brother-in-law to Joseph Goebbels. Three-hundred prisoners of war at the Luckenwalde prisoner-of-war camp, including African-Americans and French-speaking Africans, were forced to participate as extras in the film. It is not certain what happened to these soldiers after the film was shot. The Allied military authorities banned the showing of the film in Germany in 1945. However, the ban was lifted in the 1980s, when numerous Nazi propaganda films were reviewed.

The film Germanin (subtitled in English) is now available in the large Africa film collection of the African Studies Centre in Leiden. Collecting movies is one of the spearheads of the ASCL Library. Films offer glimpses of moments in African history, even in the case of political propaganda movies such as Germanin.

Further reading

- Wolfgang U. Eckart: „Germanin“ – Fiktion und Wirklichkeit in einem nationalsozialistischen Propagandafilm, in: Wolfgang U. Eckart und Udo Benzenhoefer (Hrsg.): Medizin im Spielfilm des Nationalsozialismus, Burgverlag Tecklenburg 1990, S. 69–83, ISBN 3-922506-80-1.

- Eva Anne Jacobi: Das Schlafkrankheitsmedikament Germanin als Propagandainstrument: Rezeption in Literatur und Film zur Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, in: Würzburger medizinhistorische Mitteilungen, Band 29, 2010, S. 43–72.

- Julia Okpara-Hofmann: Schwarze Häftlinge und Kriegshäftlinge in deutschen Konzentrationslagern. Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, 2004. (Date accessed: August 2020)

- Ulrich-Dietmar Madeja & Ulrike Schroeder: From colonial research spirit to global commitment: Bayer and African Sleeping Sickness in the mirror of history, In: Tropical medicine and infectious disease, 2020-03-10, Vol.5 (1), p.42

- For more publications on the African sleeping sickness see the ASCL catalogue

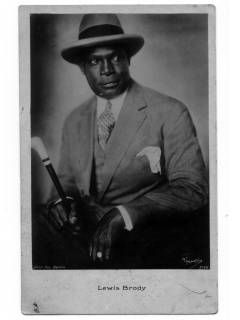

For literature on Louis Brody, the Cameroonian-born German actor who played the role of King Wapunga in Germanin, see

- Von Kamerun nach Babelsberg: Die Geschichte des Schauspielers Louis Brody. Deutsches Historisches Museum. (Date accessed: August 2020)

- Tobias Nagl: Von Kamerun nach Babelsberg. Louis Brody und die schwarze Präsenz im deutschsprachigen Kino vor 1945. In: Ulrich van der Heyden, Joachim Zeller (Hrsg.): Kolonialmetropole Berlin. Eine Spurensuche. Berlin-Edition, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-8148-0092-3, S. 220–225.

- Tobias Nagl: „Sonst wären wir den Weg gegangen wie viele andere“. Afro-deutsche Komparsen, Zeugenschaft und das Archiv der deutschen Filmgeschichte. In: Claudia Bruns, Asal Dardan, Anette Diedrich (Hrsg.): „Welchen der Steine du hebst“. Filmische Erinnerung an den Holocaust (= Medien – Kultur. Bd. 3). Bertz + Fischer, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86505-397-8, S. 156–169.