Southern African liberation struggles : contemporaneous documents, 1960-1994

In 1980, when she was 12 years old, Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila left Namibia to join the liberation struggle. Too young for the military, she was sent to a SWAPO education centre in Angola, then to secondary school in Sierra Leone. At 18, she was back for military training. Air bombings introduced her to the realities of war: “I thought that when I leave my home I was going to go out there, fight for my country and come back. I never really thought that I could face death there and could actually die. I thought it was like what we saw in the movies and read in the story books. However, that bombing actually taught me that, it was the war and I could die there… I was so afraid and the only thing I could do was to pray.” But she overcame her fear and joined SWAPO’s combatants at the front. In 1990 Namibia gained independence and in March 2015 she became Namibia’s fourth Prime Minister.

In 1980, when she was 12 years old, Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila left Namibia to join the liberation struggle. Too young for the military, she was sent to a SWAPO education centre in Angola, then to secondary school in Sierra Leone. At 18, she was back for military training. Air bombings introduced her to the realities of war: “I thought that when I leave my home I was going to go out there, fight for my country and come back. I never really thought that I could face death there and could actually die. I thought it was like what we saw in the movies and read in the story books. However, that bombing actually taught me that, it was the war and I could die there… I was so afraid and the only thing I could do was to pray.” But she overcame her fear and joined SWAPO’s combatants at the front. In 1990 Namibia gained independence and in March 2015 she became Namibia’s fourth Prime Minister.

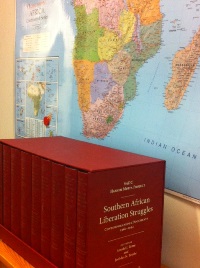

Documentation of the Southern African liberation wars

Saara Kuugongelwa’s is one of many personal stories of participants in Southern African liberation struggles that were collected on video and tape recorders between 2006 and 2010, following the Southern African Development Community (SADC) leadership’s decision in 2004 to document the Southern African liberation struggles and to publish the results in a series of books. In 2015 the impressive 9-volume work appeared, edited by Arnold J. Temu and Joel das N. Tembe, published in Dar es Salaam by Mkuki na Nyota Publishers.

The volumes 1-5 focus on the liberation wars in Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe. The volumes 5-7 document experiences in the frontline states Botswana, Tanzania and Zambia, and in the ‘extension countries’ Lesotho, Malawi and Swaziland. Each time, a historical-analytic chapter is followed by an extensive section with personal stories, not only in English, but also in Portuguese (Mozambique), Swahili (Tanzania) and Shona (Zimbabwe).

The last two volumes focus on countries and international organizations - inside and outside of Africa - that were sympathetic to and supported the liberation movements in various ways.

“Other” voices

The volumes claim to provide a comprehensive, but not an exhaustive record of the liberation struggle. In the foreword it is explicitly stated that, while the SADC states sponsored the research, it was the aim of the research project that “the resulting documentation should not […] reflect the views of the political leadership, individuals and parties currently in power to the exclusion of all others.” Whether or not the project - more or less - succeeded here remains to be seen. Among the 35 personal stories of Namibians (including SWAPO leader Sam Nujoma and others who, like Saara Kuugongelwa obtained good positions after independence), a rare dissident voice is SWAPO member Andreas Shipanga’s, who, believed to be a spy for the West Germans, was arrested by the Zambians in 1976. Shipanga, who died in 2012, is no admirer of Nujoma. His story is introduced as that of a man who was “among the group that betrayed the SWAPO people”.

In the ‘spy crisis’ of the mid-seventies, an estimated 1,600-1,800 SWAPO members were arrested by the Zambians on request of the SWAPO leadership (A history of Namibia, p. 280). Namibian pastor Salatiel Ailonga and his wife Anita, who at the time served SWAPO in a Zambian  refugee camp, saw themselves forced to flee the continent. “I know I have been doing nothing against SWAPO and its constitution or its people or the nation of Zambia”, says Ailonga in the touching documentary about the couple’s life From Namibia with love: a political love story (2011). The couple returned to Namibia in 1990, but Ailonga got sacked by the Church and faced suspicion and mistrust for many years. Anita says: “There are very many memories which people perhaps don’t know, they know the official version, they have read Nujoma’s book, but there are no small stories how it happened and what people did feel and what they did fear”.

refugee camp, saw themselves forced to flee the continent. “I know I have been doing nothing against SWAPO and its constitution or its people or the nation of Zambia”, says Ailonga in the touching documentary about the couple’s life From Namibia with love: a political love story (2011). The couple returned to Namibia in 1990, but Ailonga got sacked by the Church and faced suspicion and mistrust for many years. Anita says: “There are very many memories which people perhaps don’t know, they know the official version, they have read Nujoma’s book, but there are no small stories how it happened and what people did feel and what they did fear”.

It seems that these stories, at least for Namibia, still did not find their way to the SADC documentation of the struggle. The personal stories on offer here are nevertheless interesting. Not only for what is said - and by whom, and how - but also for what is not.

Heleen Smits