Corrective history writing: discovery by Klaas van Walraven about the 1974 putsch in Niger

ASC senior researcher Klaas van Walraven just published an article in Politique Africaine: ‘"Opération Somme" : la French Connection et le coup d’État de Seyni Kountché au Niger en avril 1974’ (English: ‘Operation Somme: the French Connection and Seyni Kountché’s Coup d’État in Niger, April 1974’). The article revisits the question of French involvement in African regime change by analyzing an example from the past: the putsch by Lt-Col. Seyni Kountché in Niger in 1974, which led to the fall of President Hamani Diori. The French were accused of involvement because Diori had had disagreements with them. During his research in the Paris archives, Van Walraven made a fascinating discovery: not only were the French not involved in the putsch, they actually started up measures for an airborne operation to save Diori, if not reinstall him, code-named “Plan Somme”.

ASC senior researcher Klaas van Walraven just published an article in Politique Africaine: ‘"Opération Somme" : la French Connection et le coup d’État de Seyni Kountché au Niger en avril 1974’ (English: ‘Operation Somme: the French Connection and Seyni Kountché’s Coup d’État in Niger, April 1974’). The article revisits the question of French involvement in African regime change by analyzing an example from the past: the putsch by Lt-Col. Seyni Kountché in Niger in 1974, which led to the fall of President Hamani Diori. The French were accused of involvement because Diori had had disagreements with them. During his research in the Paris archives, Van Walraven made a fascinating discovery: not only were the French not involved in the putsch, they actually started up measures for an airborne operation to save Diori, if not reinstall him, code-named “Plan Somme”.

What was the purpose of your research?

‘It has often been suspected, by Nigériens but also by some French observers, that the French government was behind the putsch by Kountché, which led to the fall of President Diori in 1974. By that time Diori was embroiled in various disputes with the French, notably with regard to the price paid for Niger’s uranium, so to people in Niger it seemed likely that the French were behind the Kountché putsch. However, no-one has ever taken the trouble to check this in the French archives, not even since documents pertaining to this period have become accessible. I wanted to find out whether the French knew something about the impending coup, because if so, this would affect our interpretation of the military interregnum in Niger in the 1970s-1980s, the focus of my research project. I decided to try and get permission to do research in the archives, in particular on the papers of Jacques Foccart.’

Who was Jacques Foccart?

Who was Jacques Foccart?

‘Jacques Foccart was the principal advisor on African affairs under President Charles de Gaulle. When De Gaulle came to power in 1958, Foccart became head of the ‘Secrétariat-Général des affaires Africaines et Malgaches’. In this position, he was in constant touch with African leaders, and thus supposed to be well-informed about what was going on in the former French colonies. Upon his retirement he donated all his archives to the French state. In principle, his papers are closed to the public and only accessible by way of a special procedure, decided at the level of the Élysée.’

What was it like, doing research in these archives?

‘The new central headquarters of the French archives are now located in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, a banlieu north of Paris. The reading room is enormous, and everything has been computerized; each visitor receives a badge which makes him traceable in all his moves around the building! Sometimes a supervisor was walking around me, monitoring what I was doing, because you may only take notes with the help of a pencil. You are not allowed to make photocopies or take photographs, for that matter. I have been sitting there for a week, jotting down notes. Jean-Pierre Bat, who works at the archives and has written a book about Foccart, has recently produced a splendid thesaurus of all the material that can be found in Foccart’s papers. Focusing on all of France’s former African colonies, its importance for scholars working on the immediate post-colonial era cannot be overrated.’

What did you discover?

What did you discover?

‘Amongst other things I found reports by the military attaché at the French embassy in Niamey from April and May 1974. They showed that, in spite of the French military advisors attached to Niger’s army, the military attaché was completely taken by surprise by Kountché’s putsch. Kountché and his men had put in place some deception operations: for a while several military units had been engaged in a ‘nomadic’ mission outside the capital to pursue ‘cattle thieves’, so there were fully mobilized units fielded close to Niamey without raising the slightest suspicions as to their purpose. During the night of the coup, the telephone line between the presidential palace and the bedroom of the French ambassador could not be used, as President Diori was already taken into custody by troops ten minutes into the putsch. The following morning, Foccart phoned the ambassador, but the line was broken in the middle of the conversation (it was known that the Nigérien Security habitually listened in on such telephone traffic). It symbolized how the French had lost control of the situation in Niger.’

How did the French react?

How did the French react?

‘There was fierce discussion among the French whether they should intervene. President Diori’s wife had been killed during the attack on the presidential palace and Diori himself, who in earlier days had been a De Gaulle favourite, was detained, so Foccart wanted to respond militarily. But France was in the midst of a political interregnum: De Gaulle’s successor, President Pompidou, had died just two weeks before the coup – for Kountché and his men, who had already decided to come into action before his death, this was a godsend, as this could only detract from French resolve. Thus, interim-president Poher did not want to act against the putschists, as he considered the risks too great.

However, as I was going through the putsch file, I discovered several copies of telegrams about ‘Operation Somme’, calling for the mobilization of French paratroopers in Corsica and elsewhere in France. They were destined to fly to the Chadian capital N’Djaména and from there supposed to descend on Niamey to free Diori. Presumably, this was an individual decision and action taken by Foccart. Other telegrams show that the necessary logistical measures were taken to launch this ‘Operation Somme’, but within the next two days, the French ambassador telegraphed to Paris, advising explicitly against an airborne operation as Kountché and his men were in full control. The next cable I saw contained an order to delay military action, and in the end it was broken off altogether. Probably in part because he had harboured suspicions about possible French intervention all along, Kountché had the French military base in Niamey closed within the next three months.’

What are your conclusions?

‘The French weren’t involved in the preparations for the putsch, they weren’t even aware of it. The French organized a military operation to rescue President Diori, but broke off the operation after two days. From a broader perspective, it tells us something about the complexity of French-African relations in the post-colonial era. The Kountché putsch was the first time that the French lost control over political developments in Niger since the fall of the Sawaba-run government in the late 1950s. In a way one could say that this, rather than the country’s formal decolonization in 1960, marked Niger’s real accession to political independence.’

Fenneken Veldkamp, ASC, September 2014

‘"Opération Somme" : la French Connection et le coup d’État de Seyni Kountché au Niger en avril 1974’; Politique Africaine, issue 134, 2014.

You can read the abstract here. The paper article is available at the ASC Library.

Link to full text (paid access).

Photo 1: Klaas van Walraven

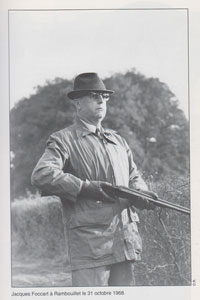

Photo 2: Jacques Foccart

Photo 3: putsch leader Seyni Kountché

Photo 4: official portrait of President Hamani Diori

Author(s) / editor(s)

About the author(s) / editor(s)

Klaas van Walraven is a historian and political scientist working on West Africa, in particular Niger. Regularly writing on current developments in Niger, he also published an extensive study on the history of that country.