Gerard C. van de Bruinhorst: On political biographies and the politics of collection development

Presidents and book launches

Presidents and book launches

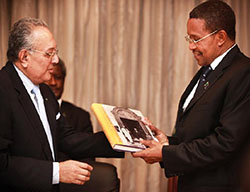

Tanzanian presidents seem to spend a lot of time in launching books during public events. The current president, Jakaya Kikwete, not only presented his own biography, (well before completion of his second term (picture #1),but also the life accounts of many others. For example:

- The personal reflections of former speaker of the National Assembly and vice-chairman of the ruling party Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), Pius Msekwa

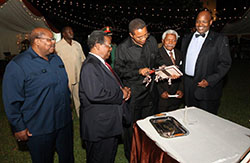

- Gijsbert Oonk’s biography of the Karimjee Family (picture #2)

- John Magotti’s biography of Rashidi Kawawa (1926 – 2009), Prime Minister of Tanganyika in 1962 and of Tanzania in 1972 to 1977

The majority of these books are biographies and autobiographies of politicians and entrepreneurs. Whereas most of these life histories are interesting in their own right, they are remarkable in another way as well. Through prefaces, introductions, and book launches by various Tanzanian presidents, these written products have been appropriated by nationalist discourses and the nationalist movement. We can quote Tanzania’s third president, Benjamin Mkapa, who wrote a foreword to Jayantilal Keshavji Chande’s autobiography “A knight in Africa”. Mkapa describes Chande as a patriot, a great Tanzanian, and a great internationalist as well as a good model to follow:

´With this autobiography, JK has given Tanzanians a unique opportunity to remember, to record, to review, and, where necessary, to rewrite the history of Tanganyika/Tanzania. The colonial archives are records of part of our history, but we must also record our own recollections, from our own multiple observation posts. I hope that this venture will inspire his contemporaries of all races to record their reflections.’

Despite this invitation to diversify and to air different views, most of these stories are very much in line with CCM policies and are rather uncritical towards the founding father of the nation, Julius Nyerere. Tanganyika’s first president Nyerere looms in the background of these books and their public presentation . For example, Msekwa’s reflections are published under the title “25 years of my public service under the leadership of Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere.” In a similar way the author of Kikwete’s biography, professor Nyang’oro, explained his motivation to write the book in comparison to Nyerere:

Despite this invitation to diversify and to air different views, most of these stories are very much in line with CCM policies and are rather uncritical towards the founding father of the nation, Julius Nyerere. Tanganyika’s first president Nyerere looms in the background of these books and their public presentation . For example, Msekwa’s reflections are published under the title “25 years of my public service under the leadership of Mwalimu Julius Kambarage Nyerere.” In a similar way the author of Kikwete’s biography, professor Nyang’oro, explained his motivation to write the book in comparison to Nyerere:

“The Father of the Nation, Mwalimu [the Teacher] Julius Nyerere, led Tanzania for 23 years and had his biography written in 1971 by William Smith. I felt it necessary to write the biography of President Kikwete with a strong conviction that it is appropriate citizens prepare the important document”

Life and times of Clement George Kahama

This process of national appropriation is also visible when George Kahama’s biography “Sir George: a thematic history of Tanzania through his fifty years of public service” was launched in 2010 by president Kikwete, who describes Kahama as ‘a man whose judgement [he] respect[s] and whose service to this nation we must all honor and appreciate”. The book launch took place with every president still living present: Ali Hassan Mwinyi, Benjamin Mkapa and Jakaya Kikwete (picture #3). The late Nyerere was represented by his wife (picture#4), thus creating a picture of a harmonious CCM dynasty preserving the legacy of “the Teacher”. His son Joseph Kahama, working in mineral development and exploitation and who is vice president of the China-Africa business council and chairman of Tanzanian royalty exploration, wrote his father’s life account. The book was published in Beijjing and has a foreword by President Kikwete, a preface by professor of political science Mukandala, and includes a personal tribute by the Secretary General of the East African Community, Juma Mwapachu. The book broadly outlines George Kahama’s professional career.

Born in 1929 in Bukoba, George Kahama completed his secondary education at Tabora Boys School (the same school Nyerere had attended a few years earlier) to study for the Cambridge School Certificate (1948-1950), together with other future first generation leaders such as Oscar Kambona, Rashidi Kawawa, and Job Lusinde. After two years as Secretary-Treasurer at the Bukoba Co-operative Union, he left for the UK where he studied Business Management and Economics, among other things, from 1952-1954. On his return from the UK, he served as the Union’s General Manager until he became Minister for Co-operative and Social Development in Nyerere’s first pre-independence cabinet. Under Mkapa, he served another term as Minister of Co-operatives and Marketing. As an ambassador, George Kahama worked in the German Federal Republic BRD (1964-1966), in China (1984-1988), as well as becoming High Commissioner in Zimbabwe (1989-1990). According to his son, the period in China was the most formative stage in his life as a civil servant. Kahama used his insights during his sojourn in China as Director of the Investment Promotion Centre in the era of liberalization (1990s). He is probably best known as Director of the Capital Development Authority which was in charge of the transfer of the Tanzanian capital from Dar es Salaam to Dodoma in the period 1972-1984. (For more information on the contents of the book, see Lawrence Cockcroft’s review in Tanzanian Affairs and Joseph Mutahangarwa’s reflections in his blog).

Born in 1929 in Bukoba, George Kahama completed his secondary education at Tabora Boys School (the same school Nyerere had attended a few years earlier) to study for the Cambridge School Certificate (1948-1950), together with other future first generation leaders such as Oscar Kambona, Rashidi Kawawa, and Job Lusinde. After two years as Secretary-Treasurer at the Bukoba Co-operative Union, he left for the UK where he studied Business Management and Economics, among other things, from 1952-1954. On his return from the UK, he served as the Union’s General Manager until he became Minister for Co-operative and Social Development in Nyerere’s first pre-independence cabinet. Under Mkapa, he served another term as Minister of Co-operatives and Marketing. As an ambassador, George Kahama worked in the German Federal Republic BRD (1964-1966), in China (1984-1988), as well as becoming High Commissioner in Zimbabwe (1989-1990). According to his son, the period in China was the most formative stage in his life as a civil servant. Kahama used his insights during his sojourn in China as Director of the Investment Promotion Centre in the era of liberalization (1990s). He is probably best known as Director of the Capital Development Authority which was in charge of the transfer of the Tanzanian capital from Dar es Salaam to Dodoma in the period 1972-1984. (For more information on the contents of the book, see Lawrence Cockcroft’s review in Tanzanian Affairs and Joseph Mutahangarwa’s reflections in his blog).

Kahama and Nyerere

What is almost completely absent in this book is a critical reflection on Kahama’s relationship with Julius Nyerere. Despite a few mildly formulated questions about Nyerere’s socialist policy, the failure of the Dar es Salaam – Dodoma capital transfer, and the inadequately functioning of co-operatives in Tanzania (p. 139), the book is rather uncritical towards Nyerere whom Kahama regarded as a close friend (p. 66). The first Tanzanian president’s role in the merger between mainland Tanganyika and Zanzibar after the bloody revolution in 1964 remains unclear. The whole union issue which has stood on the top of the Zanzibar agenda for years and still dominates the political and religion discourse of both countries , is simply described as being the initiative of the Zanzibar president Karume. According to Kahama it is ‘an arrangement which has stood the test of time’ (p. 36).

Another example of the way dissidents are being carefully circumvented in this biography is to be found in the relations with China. In1965, Nyerere and Kahama travelled to China, the first of 5 visits, which turned out to be very important for the future of Tanzania. Although China’s model was adapted to their own specifications, it heavily influenced the socialist experiment in Tanzania (1967-1983). However, the first foreign minister of Tanganyika, Oscar Kambona (1928-1997), only reluctantly supported the official transition of Tanzania to a one-party state in 1965. His opposition to Nyerere’s socialism and Chinese influence on this policy culminated in his self-imposed exile to the UK in July 1967. (Probably James Brennan’s biography of this early Nyerere ‘traitor’ will fill in many of the blanks in the story of this highly interesting antagonist).

Another example of the way dissidents are being carefully circumvented in this biography is to be found in the relations with China. In1965, Nyerere and Kahama travelled to China, the first of 5 visits, which turned out to be very important for the future of Tanzania. Although China’s model was adapted to their own specifications, it heavily influenced the socialist experiment in Tanzania (1967-1983). However, the first foreign minister of Tanganyika, Oscar Kambona (1928-1997), only reluctantly supported the official transition of Tanzania to a one-party state in 1965. His opposition to Nyerere’s socialism and Chinese influence on this policy culminated in his self-imposed exile to the UK in July 1967. (Probably James Brennan’s biography of this early Nyerere ‘traitor’ will fill in many of the blanks in the story of this highly interesting antagonist).

Christianity, Islam and the nation-state

Readers interested in how Nyerere handled criticism, such as that voiced by Chief Abdallah Said Fundikira who together with Kahama was part of the pre-independence cabinet, will be disappointed in this biography. One reason might be that both Julius Nyerere and George Kahama shared a very close connection to the Roman Catholic Church. Since Sivalon’s dissertation, this aspect of Nyerere’s policy has received ample attention. But also Kahama’s ties to the Vatican are prominently presented in his biography. The title “Sir George” refers to Kahama being knighted by the Pope’s special delegation in 1962. Tanzanian Muslims (such as Hassan bin Amir) were very critical towards Kahama’s close relationships with the Vatican (as Mohamed Said writes). According to his son, the Church has been a source of strength for Kahama:

“The church has been a solid and dependable rock in a changing world… his knighthood in the order of Saint Gregory the Great is not merely an honorific title but rather an outward sign of his deep faith and commitment to the values of the Church”.

Unfortunately it does not become clear how this commitment could have been a driving force in his policy decisions. A particular issue on which one should have expected the writer to shed more light is the sudden abolishment of the East African Muslim Welfare Society (EAMWS) by Nyerere in 1968. According to the book, George Kahama had a very close relationship with the Aga Khan, the Head of the Society, whom he had known personally for more than 30 years. By that time Kahama was General manager and CEO of the National Development Corporation and had been giving reports to the president in long monthly informal talks. It is difficult to imagine that Kahama and Nyerere did not talk about this decision, regretted by many Muslims in Tanzania today.

Libraries and the politics of collection development

Although this absence of critical reflection in Kahama’s biography could be stated as an omission, I would rather take it as a starting point to emphasize the importance of and access to, different sources written from different perspectives. “Sir George” should not be read in isolation but as part of a much wider political discourse in Tanzania, characterized by themes as varied as the CCM struggle for legitimacy the movement towards the East (the book is published in Beijing), attempts to salvage the Zanzibar/mainland union, and the place of religion in the public sphere. But above all the (political) biographies published and publicly presented by CCM statesmen deal with the legacy and memory of Nyerere, a legacy which is increasingly being contested (see Marie-Aude Fouéré’s work). This theme is not explicitly addressed in this book but as the few examples above show, its omission in the book is clearly felt. Therefor this biography, as well as the others from the first generation of Tanzania’s leaders, should be read against the canvas of all the other accounts of Nyerere’s opponents and antagonists. Offering complete access to a range of resources, or as complete as possible, and including different accounts of memories of Nyerere, will allow researchers to assess the value of a biography such as Sir George’s in a more adequate way. This is a task for the global network of public research libraries.

It might seem surprising that, according to worldcat (which claim to aggregate a collection of over 35 million unique monographs),the only public library in the world offering a copy of Sir George’s biography is the African Studies Centre in Leiden. However, several overlapping studies in global resource collections show that this scarcity is not at all an exception but unfortunately rather the rule (see, for example, http://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/publications/library/2013/2013-09.pdf) . In other words: every library in the world has titles in their collection which are not held by any other public library. That is not usually a problem for the few specialists who can acquire a copy, as recent bibliographies show: (both Thomas Molony and Brian Cooksey refer to Kahama’s life story). But libraries do not only cater for the limited number of specialists, but also for the larger academic community, students, and other interested readers. Although social media and Google (Scholar/Books) might become increasingly important in the Discovery stage of a research query, in a case like “Sir George,” which is not for sale through the normal internet trade channels, the actual Locate, Request and Deliver stages of the item remain a problem. In all four phases (from Discovery to Delivery), the public library offers essential services.

It might seem surprising that, according to worldcat (which claim to aggregate a collection of over 35 million unique monographs),the only public library in the world offering a copy of Sir George’s biography is the African Studies Centre in Leiden. However, several overlapping studies in global resource collections show that this scarcity is not at all an exception but unfortunately rather the rule (see, for example, http://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/publications/library/2013/2013-09.pdf) . In other words: every library in the world has titles in their collection which are not held by any other public library. That is not usually a problem for the few specialists who can acquire a copy, as recent bibliographies show: (both Thomas Molony and Brian Cooksey refer to Kahama’s life story). But libraries do not only cater for the limited number of specialists, but also for the larger academic community, students, and other interested readers. Although social media and Google (Scholar/Books) might become increasingly important in the Discovery stage of a research query, in a case like “Sir George,” which is not for sale through the normal internet trade channels, the actual Locate, Request and Deliver stages of the item remain a problem. In all four phases (from Discovery to Delivery), the public library offers essential services.

The fact that a book of the stature of Sir George and launched with the media attention it received, is simply missed by almost every major library in the world and after almost 5 years of publication, seems to reflect the imbalance of current global collection development. With decreasing budgets, most libraries tend to limit their efforts to supporting their own curricula. Collection development appears to be increasingly driven by the wish to survive in fast changing national economic climates than to cooperate in the international arena. “Sir George” should have been available within months of publication in sufficient quantities in order to guarantee proper circulation.

Collecting global resources in aggregated collections

Staff of the African Studies Centre’s library regularly visit diverse countries in Africa to fill in lacunae in the collection and acquire valuable works such as “Sir George.” Like all public libraries, the ASC has a limited budget, and has constraints in language and acquisition methods but within this challenging framework the ASC still manages to acquire printed publications which are not yet available in the global collection. This means though that we could not collect the valuable biography of another important poet and Tanganyika minister: Kaluta Amri Abedi (1924-1964), mayor of Dar es Salaam and Minister of Justice. The sole reason was that “Historia ya Hayati sheikh Kaluta Amri Abedi” is written in Swahili. It is disappointing that today, two years after publication it is still not available in worldcat. However, we did succeed in acquiring a copy of “Sir George,” as well as an almost complete set of the Islamic newspaper “Horizon“ , both unique according to worldcat. The first edition of Hamza Njozi’s book “Muslims and the State” is also only available at the ASC. These unique acquisitions provide much needed diverse recollections of Nyerere’s legacy, “from multiple observation posts” to quote President Mkapa again. In contrast to these rare items, a more mainstream perspective found in Mbogoni’s book is well represented in more than a hundred libraries. Collecting from a system-wide, aggregate global collection perspective will prevent this imbalance and improve access to global resources.

Gerard C. van de Bruinhorst