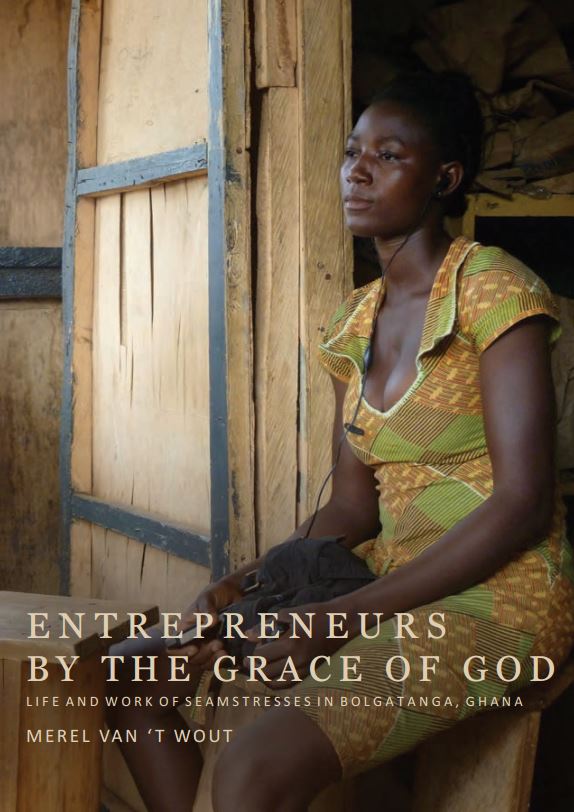

Interview with Merel van 't Wout, winner Africa Thesis Award 2015

Merel van ‘t Wout has won the Africa Thesis Award 2015 for her thesis 'Entrepreneurs by the grace of God: Life and work of seamstresses in Bolgatanga, Ghana'. She responds to our questions from Tamale, Ghana, where she is currently doing fieldwork for her PhD project '"Indisciplined" youth in Tamale: creating belonging and imagining a future'.

Merel van ‘t Wout has won the Africa Thesis Award 2015 for her thesis 'Entrepreneurs by the grace of God: Life and work of seamstresses in Bolgatanga, Ghana'. She responds to our questions from Tamale, Ghana, where she is currently doing fieldwork for her PhD project '"Indisciplined" youth in Tamale: creating belonging and imagining a future'.

What did you discover during the fieldwork for your MA thesis in terms of what drives young women in Ghana's Upper East region to start their own businesses, in particular as seamstresses?

It is crucial to acknowledge that, for many, ‘entrepreneurship’ is a necessity-driven ‘option’. Among the poor, necessity shapes and structures the size, configuration and outlook of business activities. The life stories of the seamstresses in Bolgatanga (Ghana) show that it was only after they failed to enter formal education - and thereby lost the possibility of getting a wage-paid job – that they decided to enrol in apprenticeship training. This decision was not made easily. The realization that life would not be what they had hoped for – an escape from poverty through formal education - weighed heavily on these young women. In some cases, it severely affected their self-image and becoming a seamstress symbolized failure: they had not ‘made it’ in life. The women did not see their self-employment as an opportunity’, in ‘entrepreneurship’ or otherwise.

Why does the title of your thesis emphasize the grace of God?

The title of this thesis refers to the way the girls perceive their own agency in trying to become successful entrepreneurs vis à-vis their dependence on ‘the grace of God’. Many young seamstresses in Bolgatanga felt that it was only ‘by the grace of God’ that their business activities could support their livelihood. Whether they are Christian or Muslim - all girls mentioned ‘being a God-fearing person’ as the single most important quality that would help them to succeed. While it is almost impossible to disentangle faith, discourse and the reproduction of socio-religious values, it is safe to say that many young women expressed a deep trust in the providence of God.

Why are you critical of policies to promote (female) entrepreneurship among the poor?

Taking the experiences of the seamstresses as an example, it becomes clear how interdependent – and superficial - the theoretical assumptions about entrepreneurship promotion are. Especially in a context of poverty, these assumptions (i.e. the idea that entrepreneurship leads to poverty reduction, gender equality, empowerment and economic growth) do not stand the test of reality. Thus, it is unclear why we should still consider the promotion of entrepreneurship among the poor as a viable development strategy. It probably reflects our own (Western) ideological and normative views and says more about our inclination to seek solutions for intractable problems than that it speaks to the dilemmas at hand.

There are three cross-cutting issues that need to be taken into account when we discuss entrepreneurship as a development strategy, you write. The first is that the conceptualization of ‘entrepreneurship’ in development discourse is rather weak.

There is no consensus on the question whether entrepreneurship can be taught. Instead, it is assumed that everyone who is motivated to learn can develop their entrepreneurial skills. Following from this, mere self-employment is labelled as ‘entrepreneurship’ in development discourse. However, this one-dimensional and thoroughly a-historical conceptualization of ‘entrepreneurship’ renders the term useless and narrows our understanding of the problems at hand. One should draw a clear dividing line between ‘self-employment’ and ‘entrepreneurship’ in order to move away from the high expectations that are associated with entrepreneurship.

The second issue you mention is that the socio-economic context in which ‘entrepreneurial’ activities take place is being neglected.

If there are no jobs available, people are simply forced to make a living through informal activities. Thus, the existence of a plethora of micro-businesses should not be taken as evidence for high levels of ‘entrepreneurial’ aspirations. In the case of the Bolgatanga seamstresses, their activities merely reflected their poor background and their lack of choice.

And the third issue you mention is that the importance of cultural and psychological factors is not taken into account.

Women were especially affected by the continuous struggle to obtain cash for basic necessities. The lack of cash, heavy daily schedules – filled with chores around the house - not only reduced the amount of time that the seamstresses could spend on their business, but also took a toll on their energy. Women often felt like ‘beggars’ since earnings from their work were barely enough to survive. Furthermore, hierarchical structures in Ghanaian society place seamstresses on the lower rung of the social ladder. Customers often treat them without respect or refuse to pay the full amount for their services. Patriarchal gender relations, as well as socio-religious values, prescribe respect for and obedience to (male) customers instead of standing up for one’s rights. There is a huge discrepancy between the cultural connotations surrounding the seamstress profession and the ideal of ‘empowerment’ of female ‘entrepreneurs’.

So, one of your main conclusions is that the ongoing attractiveness that entrepreneurship carries for development policymakers is misplaced.

Based on the stories of seamstresses in Bolgatanga, this thesis is an appeal to rethink policies designed to promote (female) entrepreneurship among the poor. It calls into question the portrayal of self-employment as ‘entrepreneurship’, the depiction of poverty as an individual problem and the relevance of entrepreneurial skills training to the poor. Generating money through businesses could indeed reduce poverty. The crux of the matter is, however, that the theory on entrepreneurship as a development strategy does not differentiate between self-employment and entrepreneurship. In practice, entrepreneurial theory expects impoverished, uneducated seamstresses to come up with innovative business plans, raise the required money, break hierarchical and patriarchal structures and lift themselves out of poverty; consequently, it misplaces responsibility and misjudges the situation.