The politics of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement

Chibuike Uche is the chairholder of the Stephen Ellis Chair for the Governance of Finance and Integrity in Africa.

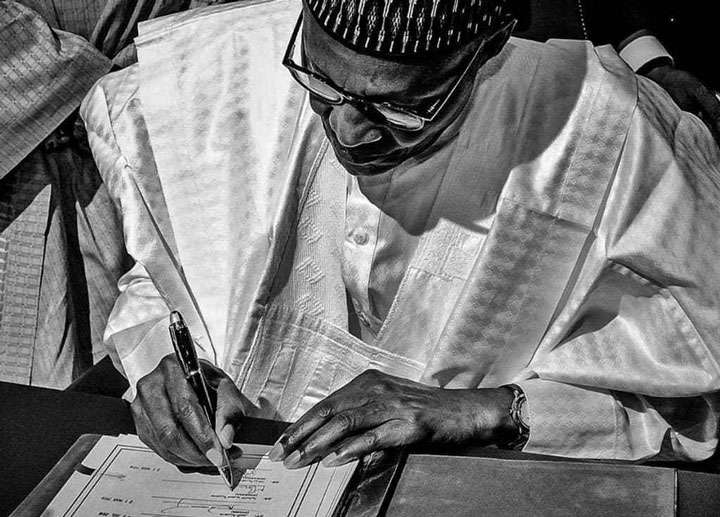

In July, Nigeria, which is the largest economy in Africa, signed the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA). With this development, Eritrea is now the only African country that has not acceded to the treaty which was opened up for signatures in March 2018. While signing the agreement, Nigeria’s President Buhari made it clear that the country was mainly concerned with ensuring that free trade should also be fair trade.

Concern over exploitation

Nigeria’s reservations about AfCFTA have to do in part with its concern that such a scheme can be exploited by some non-African countries or groups that have been pushing for free trade with Africa. Nigeria, for instance, refused to sign the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) between the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the European Union (EU), arguing that it will frustrate industrial development and local job creation. A major concern with fair trade in Africa has to do with the definition of what constitutes goods produced in Africa. It is, for instance, easy for non-African economic actors to exploit the institutional weaknesses in their beneficiary African states in order to enable their goods and services qualify as goods produced in Africa.

Nigeria compared to Benin

In order to appreciate the impact of non-African benefactor states on the dynamics of economic relationships among African states, we will examine the relationship of Nigeria (population: 190.9 million) and Benin (population: 11.1 million). While Nigeria was colonized by the British, Benin was colonized by the French. In addition to being neighbours, both countries are also members of ECOWAS. It is instructive that the establishment of ECOWAS was championed by Nigeria mainly because it wanted to curtail the influence of France in the sub-region.

Convertibility of the CFA Franc

The conflicting objectives of Nigeria and France in West Africa arguably explain why many of the objectives of ECOWAS have not been achieved. One way France has been able to retain the loyalty of its ex-African colonies has been by guaranteeing the stability and convertibility of the CFA Franc. The existence of a common currency has ensured close economic and monetary cooperation among the Francophone West African states. This explains why the long-running attempt at monetary integration in ECOWAS has not gone beyond the drawing board. Although the ECOWAS Trade Liberalization Scheme has since been signed, it is rarely respected by member countries. Similarly, the Common External Tarrif signed by ECOWAS member countries has also been harphazardly implemented. It is as a consequence of this that legal and illegal goods destined for the Nigerian market are routinely imported via the Port in Benin.

Percentage of local raw materials

It is in order to prevent the legal parts of proxy and/or arbitrage trade from occurring within AfCFTA that South Africa suggested that only goods with at least 80 percent of local raw materials should be considered as goods produced in the continent. The reality, however, is that the economic production systems of most African countries are less able to internalize their supply and value chains to achieve such high thresholds. This is arguably why ECOWAS, Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) and Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMMESA) currently have minimum local raw material content requirements of 60 percent, 40 percent and 40 percent respectively. Reconciling these wide variances in practices and expectations will be easier said than done.

Surprising speed of endorsement

It is in the light of the above that I consider the speed with which most African countries endorsed AfCFTA and the widespread global support and acclaim it has received, to be surprising. One possible explanation is that the interests of non-African actors may be the major driving force behind AfCFTA. This is arguably because trade liberalization within Africa could be an important first step towards achieving trade liberalization between Africa and such countries, which is their desired goal.

Dealing with Africa as one unit

Circumstantial evidence that supports this hypothesis can be found at several levels. First, many powerful benefactors of Africa like China, USA, India and EU have increasingly shown preference to deal with Africa as one unit. It is also instructive that the EU, which has been having difficulties getting most of the sub-regional blocs in Africa to sign the EPA, is now a major financier and supporter of AfCFTA. Pro-EPA countries like Kenya and Ghana are also leading the charge for the establishment of AfCFTA. Furthermore, the two pan-African institutions that are at the forefront of championing AfCFTA, the African Union and the African Development Bank, depend heavily on non-African donors for their survival. It is also surprising that many African countries have been quick to endorse AfCFTA even though they have been unwilling to consent to the far less significant scheme of visa-free travel of Africans within the continent. Finally, the present AfCFTA goes against the original bottom-up approach to first strengthen the sub-regional free trade zones and then gradually merge their operations.

Interests of African countries

Although an African-wide free and fair trade regime can help stimulate Africa’s economic development, this is unlikely to happen unless it is driven by the interests of African countries. There is thus a need to first address the problems of the continent’s sub-regional trading blocs with the view of strengthening their operations and enhancing their developmental value.

Top photo: Nigeria officially joins AfCFTA as President Buhari signs the Agreement. Photo credit: Ivotesng.com

This post has been written for the ASCL Africanist Blog. Would you like to stay updated on new blog posts? Subscribe here! Would you like to comment? Please do! The ASCL reserves the right to edit, shorten or reject submitted comments.

Comments

Add new comment

Dear Uche,

Thanks for your thought provoking writeup. You have raised important issues regarding AfCFTA. I also have some scepticism in many areas but most importantly on institutional weakness. In a free trade area, the elimination of tariffs and technical barriers cover only goods that originate within the free trade area. However, in the AfCFTA, I am concerned that goods would be imported into Africa, repackaged as made in Africa, and circulated within the FTA, without proper checks. I doubt if there would be functional mechanisms in place to address these kinds of issues. A continental free trade agreement without a continental customs union is a disaster.

The signing of the Agreement establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) by 44 African countries in Kigali, on March 21, 2018 inrush the enters the third step of the implementation of AEC and attests of a strong desire to deepen regional integration in Africa. As mentioned in article 3 of the AfCFTA agreement, the key objective of the AfCFTA is to boost intra-African trade. However, to achieve this goal, many challenges need to be addressed and in particular the setting up of a single continental legal trade regime. This includes the harmonization of trade procedures.

Among the factors holding back intra-African trade is document requirements, cumbersome border-crossing procedures and delays. For instance, an average ten days is needed to clear direct exports through customs in Sub-Saharan Africa and on average eight documents to import. The number of documents required importing goods and border compliance negatively affects trade volume in Africa. There is a need of harmonization of trade procedures. Bashar H. Malkawi