Rethinking Global Health in Africa: learning from history, human rights, and microbes

By Christiana Banja, student of the Research Master African Studies. She wrote this blog post as part of the course 'Thematic Fields: linking theory to practice' for the module on global health. This post appears in an (irregularly appearing) series written by students or recent alumni of the Master and Research Master African Studies.

By Christiana Banja, student of the Research Master African Studies. She wrote this blog post as part of the course 'Thematic Fields: linking theory to practice' for the module on global health. This post appears in an (irregularly appearing) series written by students or recent alumni of the Master and Research Master African Studies.

When people talk about ‘global health’, Africa often becomes the focus. This is not new. For over 100 years, the world has treated Africa as a place full of health problems that need fixing, whether it was during the colonial period, during disease outbreaks like Ebola or COVID-19, or in new programmes run by international health groups. However, many of these health solutions don’t consider the voices of African people. They often ignore local knowledge, history, and the everyday struggles of communities.

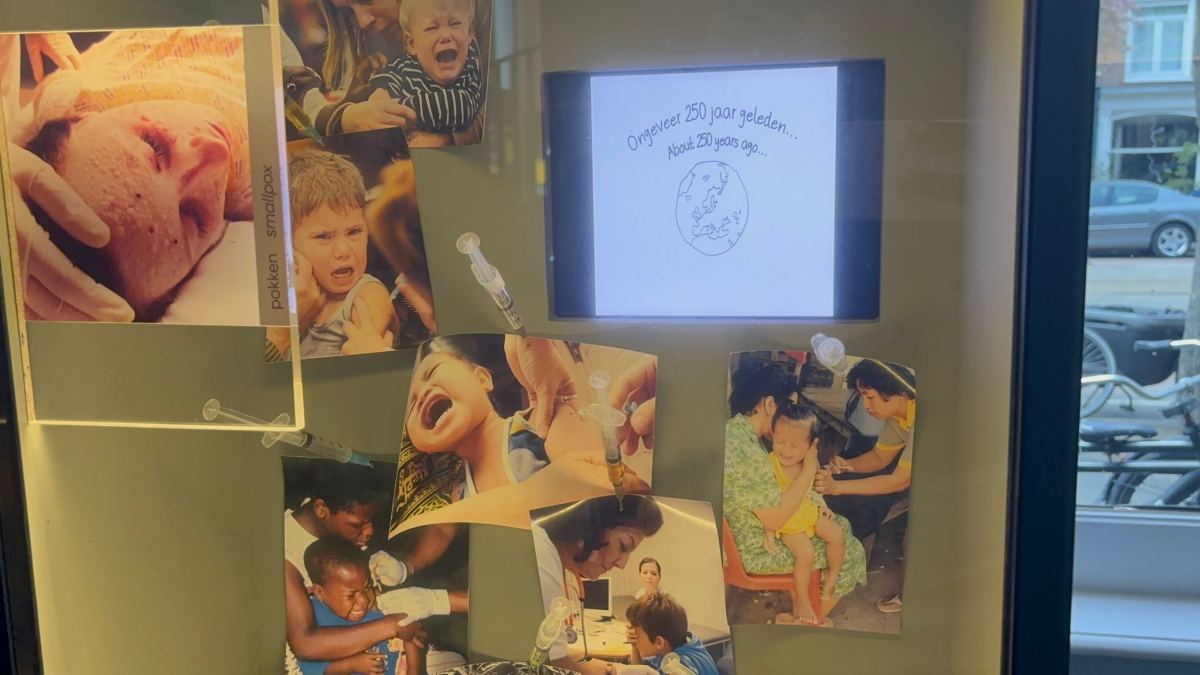

This blog looks at how global health has been shaped in Africa. I draw ideas from the Global Health in Africa course of the Research Master African Studies, especially three main lectures we had, and I also include what I learned from visiting Micropia, a museum in the Netherlands that focuses on microbes (tiny living things like bacteria and viruses). By connecting ideas from history, law, social science, and even science museums, I argue that we need to think differently about health in Africa: one that is fair, respectful, and includes everyone’s voice.

The colonial roots of global health

The colonial roots of global health

To understand today’s health challenges in Africa, we need to look back at history. In the 1800s and early 1900s, European countries had colonies in Africa. They introduced health systems not because they cared about Africans, but to protect their own people (mainly the white settlers and soldiers) from diseases. Health laws and hospitals were mostly for the Europeans, while Africans had very little access to care. Local medical knowledge was often ignored or called ‘unscientific’. In our class, one of the lecturers (Dr Sara de Wit) explained how global health grew out of this colonial past. After World War II, the World Health Organization (WHO) was created, but the same power structures stayed. Wealthy countries and donors, like the Gates Foundation, now play a big role in deciding what health programmes should be set up in Africa. Even today, decisions about diseases and vaccines are often made in Europe or the U.S., with little input from African countries. This history shows that global health is not just about medicine, it is also about power and who gets to decide what’s important.

Human rights, inequality, and the COVID-19 lesson

Health is not just about treating diseases, it’s also a basic human right. Everyone, no matter where they live, should have access to good healthcare. But in real life, that’s not the case. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw clearly how unfair the system is. Rich countries bought and kept most of the vaccines, while poor countries, especially in Africa, were left behind. This situation became known as ‘vaccine apartheid’, a term that shows how deep the divide was between the rich and the poor. In our first lecture, Dr Sheila Varadan explained how laws that are supposed to protect people’s rights were not always followed during the pandemic. For example, some countries used strict rules to control movement and gatherings, which ended up hurting vulnerable people the most, like poor families, women, and children. These actions were supposed to protect public health, but they also took away freedoms without much care for the people affected.

The pandemic showed that even when human rights are written in law, they can be ignored. It made people ask: What kind of health system are we building if it only works for the rich?

Real-life health challenges and why local knowledge matters

Many people believe that science alone can fix health problems. But in real life, health is not just about medicine or hospitals, it’s also about people’s beliefs, culture, and how they live their everyday lives. In our third lecture, Dr Miriam Waltz introduced us to critical global health. This means asking important questions like: Who makes the health programmes? Who do they help most? And who gets left behind? Anthropologists like Ruth Prince have shown that when global health programmes reach African communities, they often don’t work as planned. Why not? Because these programmes are usually created in far-away offices without asking the people they’re meant to help.

The Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone

A good example is what happened during the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone (2014–2016). During the outbreak, international health teams rushed into the country with good intentions. They brought doctors, nurses, medicine, and rules for how to stop the virus from spreading. But many people in local communities did not trust these outsiders. Some believed Ebola was caused by witchcraft, or that it was a trick by the government. Others were scared because the health workers wore full-body suits and took away sick family members, who never returned.

Funeral practices also became a major problem. In Sierra Leone, it is very important for families to wash and touch the bodies of their loved ones before burial. But this practice helped spread Ebola, which passes through contact with body fluids. Instead of working with communities to find safer ways to honor these traditions, many health teams banned the funerals completely. This caused anger, fear, and even violence in some places. People began hiding sick relatives, which made the outbreak worse. The Ebola crisis showed that science alone is not enough. Local knowledge, culture, and trust matter just as much maybe even more. If the health teams had worked closely with local leaders and listened to people’s fears and ideas, they might have saved more lives. Also, during the outbreak, many African researchers helped collect data and talked with families to understand what was happening on the ground. But most of these researchers were not included as authors in reports or given leadership roles. Dr Kalinga, one of the scholars we studied, explained how hard it is for African researchers to get proper credit, even when they do the most important work. They are often treated as ‘assistants’ instead of experts. All of this teaches us one big lesson: health programmes must include the voices of the people they are meant to help. Respecting local culture, listening to community leaders, and giving African researchers a seat at the table is not optional, they are essential. Without trust and inclusion, even the best science can fail.

Learning from Micropia: What tiny creatures can teach us about Big Health Problems

Learning from Micropia: What tiny creatures can teach us about Big Health Problems

During our visit to Micropia, a science museum in Amsterdam (the only microbe museum in the world), I saw the invisible world in a whole new way. Micropia is all about microbes: tiny living things like bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa that live all around us and even inside our bodies. At first, you might think: ‘Why should I care about something I can’t even see?’ But what I learned changed how I think about health, sickness, and even how we treat nature. We are often taught that microbes are our enemies. We are told to wash our hands, use sanitizer, take antibiotics, and kill germs to stay safe. But is it really that simple? Micropia shows us that microbes are not all bad. In fact, we need them to survive. Some microbes help us digest our food, protect our skin, and fight off harmful bacteria. They help plants grow, clean polluted water, and even make bread, yogurt, and cheese. This raised a big question for me: Why do we focus only on the harmful microbes and ignore the good ones? Are we trying too hard to kill something we actually need?

This question becomes even more important when we think about how antibiotics are used in many parts of the world, including in Africa. In countries with weak health systems, people often buy antibiotics without a doctor’s prescription. Sometimes they take them for the wrong illness or stop taking them too early. Why? Because they don’t have access to proper healthcare, or because they don’t trust the system, or simply because there are no doctors nearby. Health experts like Mendelson and Chandler (2024) talk about a growing problem called Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). This happens when bacteria get used to antibiotics and stop responding to them. That means even simple infections, like a cut or a sore throat, can become deadly, just like they were in the past, before antibiotics were discovered. In this new world, diseases we thought were under control could come back stronger.

But here’s the bigger issue: Is the problem only about misusing medicine? Or is it also about how our societies are structured? Think about it. If people had clean water, better toilets, and good hygiene education, would they still need to rely so much on antibiotics? If clinics were easy to reach and doctors took time to explain things, would people use medicine more carefully? This leads to a deeper question: Is antimicrobial resistance a medical problem, or a social one? The answer is both.

Balance between humans, microbes, and the environment

Micropia didn’t just teach me about microbes, it taught me to think differently. It reminded me that health is not only about fighting diseases; it's also about creating balance between humans, microbes, and the environment. Just like in nature, where every plant, animal, and microbe plays a role, our bodies need balance too. When we try to control nature too much, we sometimes make things worse. So maybe the real lesson from Micropia is this: instead of trying to kill all microbes, we should learn to live with them. We should respect them, understand their role, and work with nature instead of against it.

We should begin to ask ourselves important questions about the way we think about health. What if our approach focused more on prevention and balance with nature, rather than only on curing diseases and controlling infections? Imagine if health programmes didn’t just give out pills and injections, but also included education about microbes, helping people understand how these tiny organisms work and why some of them are essential to life. Most importantly, how can we make sure that this kind of valuable knowledge reaches everyone, including people in rural villages and low-income communities, and not just those who can afford to visit places like Micropia?

Not everything that matters can be seen…

Not everything that matters can be seen…

Walking through Micropia, staring into microscopes at the invisible life on and around us, I realised something simple but powerful: not everything that matters can be seen. It made me wonder: if we can’t even see these creatures but they still have so much impact on our lives, how much more are we missing when we ignore the wisdom of local people, the struggles of African communities, or the voices of African scientists?

Global health in Africa needs more than medicine, it needs a transformation. We can no longer rely on outdated methods shaped by colonial ideas, where solutions are imported without understanding the people they are meant to serve. It's time to break free from the ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach and build a system that reflects the realities and dreams of Africans.

So where do we start? We must begin by acknowledging our past, how health systems were shaped during colonial times, and how some of those power structures still remain. We must respect and uplift African researchers, not just use them for data collection while decisions are made in foreign boardrooms. We must listen to communities, especially in rural areas where people are often treated as problems that need to be fixed, instead of partners in building solutions.

Educate everyone about microbes!

We must also protect human rights, especially during emergencies like Ebola or COVID-19, where fear sometimes leads to harmful actions like quarantining whole villages without consent, or forcing treatments people don’t understand. And finally, we must educate everyone about microbes, not just scientists or museum visitors, but also children in classrooms and parents in markets. When people understand how bacteria and viruses work, they can make better choices and we can reduce the misuse of antibiotics that fuels antimicrobial resistance.

This journey has made me feel hopeful, but also responsible. As someone from the Global South, I carry not just my knowledge, but my lived experience. I believe that true health can only happen when we work with people, not on them. When we create space for local ideas and lived realities. When we ask hard questions like: Who is at the table? Who is missing? And why?

In the end, building a better path for global health isn’t just about fixing systems. It’s about changing hearts and minds, about replacing fear with understanding, and replacing control with care. It’s about dreaming together of a world where everyone, no matter where they live, has the chance to live a healthy, dignified life. And I believe we can get there if we choose to walk that path together.

All photos taken by Christiana Banja at Micropia-Artis, Amsterdam. Text on the lowest photo: 'I now assume with greater certainty that a human being originates not from an egg but from an animalcule that is found in male sperm', Anthoni van Leeuwenhoek, 9 june 1699.

This blog appears in the ASCL Africanist Blog. Would you like to comment? Please do! The ASCL reserves the right to edit, shorten or reject submitted comments.

Add new comment