In pursuit of excellence in Kenya’s Environmental Studies

Ton Dietz is Emeritus Professor of the Study of African Development at Leiden University, and a former director of the ASCL. He is co-organiser of the Africa Knows! conference.

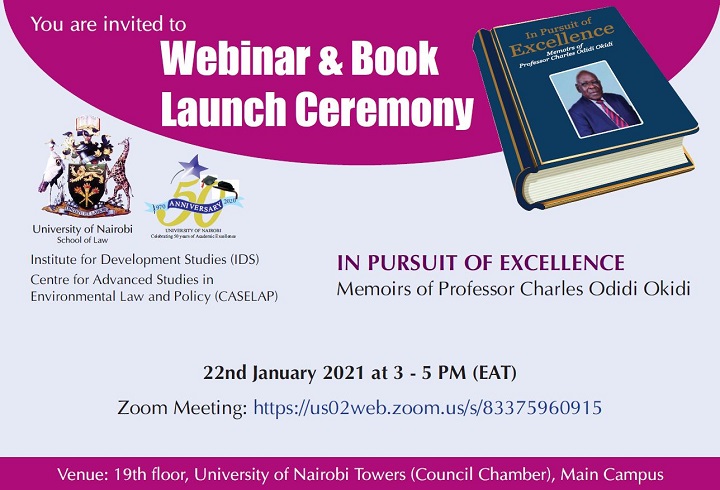

In the midst of the ongoing (virtual) ‘Africa Knows!’ conference, I was asked to say a few words during a webinar on the occasion of the book launch of the Memoirs of Professor Charles Odidi Okidi in Nairobi, on 22 January 2021, entitled In Pursuit of Excellence. Professor Okidi was the Dean of the School of Environmental Studies (SES) of (then) Moi University in Eldoret, Kenya, between 1989 and 1994. From 1991 onwards first the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs and later NUFFIC supported this School (and the University as a whole). I was the scientific coordinator of the environmental studies support programme on the Dutch side, working from the University of Amsterdam (UvA), between 1991 and 2003.

African academic hero

Okidi’s Memoirs are a testimony of academic leadership: at the University of Nairobi, at Moi University, at Karatina University and at the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), where he was responsible for stimulating the institutionalisation of environmental laws in many African countries. For me, Charles Okidi is one of Africa’s academic heroes.

What has become of the graduates?

At the end of Okidi's book chapter about his pioneering work at the School of Environmental Studies at Moi university, he writes: ‘It is desirable that a tracer study be done to find out what has happened to those who went to Amsterdam under the project. Where are they?’ (p. 154).

The good thing about being a pensioner is that I had some time to find out how far I would get by doing that tracer study, just by making use of a ‘deep search’ on the wonderful internet. And although some things are still unclear, I think that my search brings us very close to an answer to Okidi’s question.

Tracing the students

I looked at three categories of people in the collaborative programme: scholars in the staff development programme (11), DPhil students in the NUFFIC programme (4), and a group of special MPhil students: every year two women and two students from Kenya’s arid and semi-arid areas; (21). In addition, I looked at a few extra people from Moi University whom we supported with extra funds (3). And finally I looked at the other pioneers in the School's own DPhil programme, because they also benefited a lot from the support, and were a direct consequence of the success of the School in those early years (17). Altogether, I included 56 people in this long-term tracer study.

The first question to answer of course is: how many made it to a degree? At the Master's level they were 14 out of 21, as far as I could find out, and out of those a remarkable number continued with a successful PhD or DPhil degree in Kenya and elsewhere. At the doctoral level they were 30 out of 35. In total, 44 people graduated successfully: almost 80 %. I find these results very encouraging.

Academic positions

The next question is: how many of these 56 people still work in universities? Four people have died so far (all four graduates), and from the 52 still alive (and from the 40 who graduated), 29 currently have positions as lecturers, senior lecturers, associate professors and professors at Universities, and almost all those positions are in Kenya, the large majority being with environmental programmes (Eldoret, Nairobi, Njoro, Karatina, Bondo, Maasai Mara). Most of the graduates who do not work in universities at the moment, did so for a while after graduation, but they later moved to functions in government, business, and/or NGOs, almost all in environmental functions. So: SES had a major impact on building a strong foundation for environmental studies in the country.

Cynical voices

Brain drain has always been a major worry for support programmes like these. Certainly in the beginning there were quite some cynical voices who were sure that the Dutch support to a Kenyan university’s postgraduate programme would only mean that Kenyan scholars were being prepared for the American academic job market. If we look back now, we can say that this has hardly happened: out of the 52 people still alive, only six work abroad currently: two in the USA, two in South Africa, one in Uganda, and one in Ethiopia, the last one for an Africa-wide organisation. All of these people had also worked in Kenya some time, and most of them still support the Kenyan academic sector in their current jobs abroad. It is also remarkable that out of the initial 56 scholars, some worked as postdocs in Europe for some time, but afterwards all returned ‘home’.

Defining excellence

In line with the title of Okidi’s book, ‘in pursuit of excellence’, we can also ask ourselves: how excellent have the graduates become? Of course, it is always difficult to define ’excellence’ properly. I did it the simple way: I looked at four ways to define excellence: research excellence, teaching excellence, excellence in knowledge leadership and societal excellence. For each one I used one, two or three stars. The highest category (three stars) for research excellence is: publications with altogether more than 100 citations according to Google Scholar; for teaching excellence: (associate) professorship; for knowledge leadership: position as a Dean or Director of a knowledge institute; and for societal excellence: a major position in a government or NGO institute.

For 44 graduates this resulted in:

Research excellence: 15

Teaching excellence: 9

Excellence in knowledge leadership: 8

Societal excellence: 11

And in some cases these overlap.

More than half of all 44 graduates were excellent in at least one field: 23 of them, and most of the graduates are mid-career people now, so they can still ‘grow’ in performance. I think these findings are very interesting, encouraging, and worth sharing. The Dutch support to environmental studies in Kenya in the 1990s has resulted in a considerable group of excellent scholars in the 2020s, who are a broad basis for environmental management and further environmental studies in Kenya, and in Africa as a whole, for many years to come.

Africa Knows!

Of course, with the current ‘Africa Knows!’ motto in mind (‘It’s time to decolonise minds’), I asked myself: how did we do that from 1991 onwards? We were very fortunate to work with a strong African knowledge leader, who already had made a plan, and simply asked us (and the funding agencies) to agree with that plan or otherwise leave, and who would not tolerate any sign of a colonial attitude. The plan made a lot of sense to us, so we did not leave. It is fair to say that first the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs and later NUFFIC was very generous to follow many of the ideas of Prof. Okidi, and put the Kenyan university and its long-term plans centre stage. Only during the last few years there was some pressure to go against the wishes of the Kenyan staff, e.g. in pushing for a more ‘competence-based curriculum’ (NUFFIC was ahead of its times then; now this has been widely accepted).

‘A broker on the spot’

One element that could be explained as ‘colonial’ was the involvement of Dutch resident visiting professors (four in a row), but this was a shared wish of both the Amsterdam and Eldoret leadership, ‘to have a broker on the spot’. The Kenyan Dean of the School accepted the strict financial discipline that the Dutch funding agencies (and the University of Amsterdam) demanded, but that was also to avoid financial ‘interference’ from the side of the central university leadership. There was ample support for the multi- and interdisciplinary approach to environmental studies, with ‘soft landing’ after graduation (to avoid frustrated graduates who would be drowned in teaching immediately), for adequate machinery for the science-based environmental subjects, for the School’s own library, for fieldwork stations elsewhere in the country, and for an environmental impact assessment course that was very hands-on, and with a lot of excursions and fieldwork. Interestingly, many Dutch students participated in that course as well, forming joined writing teams with their Kenyan colleagues for examination texts (to many quite an experience and often it confronted them with their prejudices and own working styles). And the staff development fellows got a chance to visit environmental agencies and university departments in the UK, Poland, the Czech Republic, Israel, and the Netherlands. As Dutch people involved in the coordination, we refused to be involved in the selection of the candidates - that was the responsibility of the local university. We insisted on joined Kenyan-Dutch supervision of the staff development fellows (who would graduate in the Netherlands) and the DPhil students (who would graduate in Eldoret) and from the Dutch side by the best person available, so looking also beyond the University of Amsterdam.

Strong leadership and an experimental attitude

In hindsight we can say that a colonial mindset and colonial practices simply did not get a chance due to the strong leadership from the Kenyan side, and we were lucky to work with key people in the Dutch funding agencies who dared to try an approach that was new to them, away from the often Dutch-driven, and ‘money decides’ attitudes of earlier periods. It was this experimental and flexible attitude from both sides that obviously helped to arrive at the current very positive results of this long-term collaboration.

Would you like to stay updated on new blog posts in the ASCL Africanist Blog? Subscribe here! Would you like to comment? Please do! The ASCL reserves the right to edit, shorten or reject submitted comments.

Comments

Add new comment

Prof Don Dietz,

I am one of the products of the Dutch and Moi University, School of Environmental Studies collaboration and I attest to academic excellence and research excellence achieved by the programme. I will participate in the populating the tracer study together with my colleagues here at University of Eldoret, Kenya.

Great

Dear Prof Ton

I am a holder of MPhil from MUSES. I proceeded to acquire my PhD in Environmental Policy from the Center for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELAP) of the University of Nairobi still under Prof Okidi. Therefore, I am a proud product of both MUSES and CASELAP both established by Prof Okidi. I do research in green and circular economy promotion in Kenya

Well scripted Professor. I am a product of the now defunct SES. Even though I graduated in 2010, I heard of the pioneer work of Prof Okidi. He did an excellent job that laid the foundation for academic excellence.

This is a very thrilling account of successful academic collaboration/international cooperation between Kenya and the Netherlands to grow academic talent for the future. Obviously, such initiatives are many but success is rare. It is also an example of collaboration in a decolonized set-up.

Of course, one problem with collaborative initiatives is the lack of continuity, even after successful results. Therefore, it is prudent to ask: what happened to the idea? Have there been similar initiatives elsewhere or did the money simply run out? was the collaboration terminated jointly by Dutch and Eldoret or was it a Dutch initiative that ran on a fixed timeframe whose termination was also the prerogative of the Dutch authorities? Just my loud and random thoughts.