Tropical oppressors: State violence in Equatorial Guinea

Joseph Mangarella is a PhD candidate at the African Studies Centre Leiden. He is a regular contributor to Brill’s Africa Yearbook, where he reports on Equatoguinean politics, economics, and society. He has written this blog on behalf of the Collaborative Research Group Rethinking African History.

Nestled between Gabon and Cameroon on the Gulf of Guinea lies Africa’s richest state per capita, Equatorial Guinea. One of the most biodiverse countries on the planet, it also bears one of the continent’s tiniest populations, with estimates ranging from 800,000 to roughly 1.2 million. To untrained eyes, it is the picture of pristine rainforest, rich aquatic life, and a peaceful, maritime culture. But it is governed by the continent’s longest serving non-monarchical head of state, assisted by one of the continent’s most corrupt and violent ruling clans. Recent developments suggest that, if gone unchecked, respect for human rights could sink to a new, frightening low.

Recent historical background

Geographical determinism is not unheard of in African Studies, and its contributions have been appropriately relativized. But it is difficult to ignore the horrible juncture of history and geography that has befallen this small nation isolated by language (Spanish), natural boundaries (islands and rain forest), a culture of bureaucratic opacity, and predatorial state security services. Since President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo took power in 1979 after deposing and condemning to death his uncle, the Essangui clan has managed to bridge the pecuniary gap from fiscal desperation in the 1980s to resource-led windfalls in the 1990s. In a comparatively sedate portent of things to come, World Bank envoy Robert Klitgaard felt compelled to publish his own accounts of the country’s mismanagement and corruption in Tropical Gangsters (Basic Books, 1990), which one reviewer called a story of ‘the nicest possible World Bank consultant in the worst of all political and economic scenarios you could imagine’.

Oil proceeds

After the discovery and exploitation of the giant Zafiro offshore oilfield, the corrupt disposition of the ruling family also turned violent. Oil proceeds were used to prop up the regime with security and surveillance, which at once created both political stability and a terrorized population. Now, with its oilfields in sharp decline, the country is returning to the fiscal imbalances which set the stage for its last successful coup. But with the regime better endowed than it was in 1979, a family more envious of its own stature, and an inner circle not this paranoid since the last failed coup attempt of 2004, the danger of state violence has been elevated. As a consequence, respect for human rights in the country - already in a sort of nadir by world standards - is bottoming out. The international community would do well to take note.

Repression

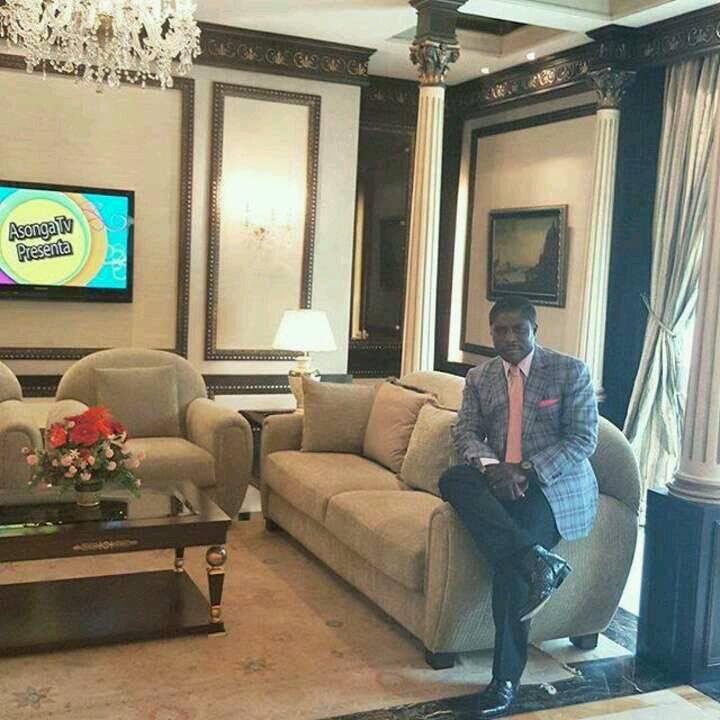

Three recent developments have coalesced to encourage state lawlessness, often resulting in unjustified loss of life and impoverishment. First, the larger context of depleted oilfields and falling production since 2014 has led the regime to rely less on patronage and more on repression. The two opposition parties, only one of which is ‘legal’ and neither of which have a single seat in parliament, have been regularly harassed by state security services, while civil society - even artists - are threatened and cajoled. In addition, the state has partially serviced its debts by cutting further social handouts and reducing abysmally low health and education expenditures. The second development is the inexorable rise of jet-setting, Instagram-active, and international convict (see France, e.g.) Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue (‘Teodorín’). The preferred son of President Obiang and the influential First Lady, Teodorín was made First Vice President in 2012 thanks to an enabling constitutional amendment in 2011. Like his father before him, Teodorín has enjoyed increasing powers of arrest and decree as the head of national security, and stands ready to succeed the presidency as the country’s very own dauphin. Third and most recently, another attempted coup was foiled in December 2017, unleashing the regime’s ire and launching a renewed era of suspicion and repression.

Three recent developments have coalesced to encourage state lawlessness, often resulting in unjustified loss of life and impoverishment. First, the larger context of depleted oilfields and falling production since 2014 has led the regime to rely less on patronage and more on repression. The two opposition parties, only one of which is ‘legal’ and neither of which have a single seat in parliament, have been regularly harassed by state security services, while civil society - even artists - are threatened and cajoled. In addition, the state has partially serviced its debts by cutting further social handouts and reducing abysmally low health and education expenditures. The second development is the inexorable rise of jet-setting, Instagram-active, and international convict (see France, e.g.) Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue (‘Teodorín’). The preferred son of President Obiang and the influential First Lady, Teodorín was made First Vice President in 2012 thanks to an enabling constitutional amendment in 2011. Like his father before him, Teodorín has enjoyed increasing powers of arrest and decree as the head of national security, and stands ready to succeed the presidency as the country’s very own dauphin. Third and most recently, another attempted coup was foiled in December 2017, unleashing the regime’s ire and launching a renewed era of suspicion and repression.

Escalating human rights abuses

For anyone even vaguely familiar with political and human rights in Equatorial Guinea, the term ‘draconian’ feels redundant. State violence and repression, typically culminating in extended prison terms and torture sessions at the infamous Playa Negra prison, have been the country’s postcolonial norm, with the effect of entrenching a one-party state which routinely enjoys cartoonish landslide electoral victories. But legislative elections, December 2017’s failed coup attempt, and future uncertainties (economic and political) have combined to unleash even more state violence, which is particularly directed at a disorganized and often fragmented opposition.

Only one legal (nominal) opposition party, the Convergencia para la Democracia Social (CPDS), remains, after the Ciudadanos por la Innovación (CI) was disbanded in February 2018. Since the legislative elections of November 2017, scores of both CPDS and CI members have been subjected to arrest and detention without charge, while journalists covering their events have had their equipment confiscated. One month after the failed coup attempt of December 2017, CI member Santiago Ebee Ela died in custody after being subject to torture. Joaquin Elo Ayeto, a human rights activist associated with the CPDS, was detained and released without charge in June 2017. Last February, Joaquin was detained again and accused of plotting to kill the president. Amnesty International claims he has been tortured several times, and since 2 March he has not been allowed to see his family. Since the failed December coup, even members of the ruling party have been regularly monitored and had their movements restricted by decree.

Alfredo Okenve’s ordeal

Alfredo Okenve’s ordeal

Neither were civil society activists spared the crackdown, and Alfredo Okenve is a case in point. Leader of the Centre for Development Studies and Initiatives (CEID), which routinely criticizes the regime for its human rights abuses, Okenve was detained for weeks in April 2017 for violating the government’s indefinite suspension of CEID’s activities. CEID was also a member of the local steering committee for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). But Okenve’s ordeal did not stop there.

During a November 2018 workshop in Libreville attended by myself and ASCL Senior Researcher Klaas van Walraven, participant Enrique Okenve (University of the West Indies-Mona, Jamaica) detailed the arrest and severe beating of his uncle Alfredo. Okenve was stopped by state security services outside mainland Bata on 27 October 2018. After removing him from his car at gunpoint, the agents dragged him into the woods and continued beating him in the face and limbs with the butts of their guns and other blunt objects. The agents’ intended victim was, in fact, Enrique’s father, CEID activist Celestino Okenve. When the agents realized their mistake, they were instructed to abandon Alfredo in the woods with broken legs and several other traumas. He thereafter underwent treatment in Madrid. Last month, France and Germany sought to award Alfredo with the Franco-German Prize for Human Rights in Malabo, but before the 15 March ceremony could take place, authorities intercepted Okenve, placed him in handcuffs, and shipped him via military plane back to mainland Bata.

Call for Action

As Mayke Kaag pointed out in her ASCL blog posted on 28 March, ‘the world is one, still divided, and connections are between nodes that are uneven in terms of power and voice’. Perhaps nowhere is this more the case than in Equatorial Guinea, a statistical void where roughly three-quarters of the population are said to live in poverty, despite boasting the highest per capita income on the African continent. Access to clean water is scarce and educational attainment is depressingly rare for the vast majority of the population, while villas and palaces dot the island landscapes. The EU, US State Department, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and various other international organizations have raised the alarm and criticized the regime, but it remains irrepressible and buoyed by the support of powerful oil majors such as ExxonMobil. If the Western oil majors could not be convinced to withdraw investments, the depletion of the country’s oilfields will certainly do so. And with the departure of oil majors goes one of the very few levers human rights activists may have had to rein in this criminal regime. Only political and moral consciousness, combined with an uncynical desire to act, can now avert further atrocities.

Photo credits:

Top photo: Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, President of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, addresses the general debate of the United Nations General Assembly’s seventy-third session, 27 September 2018. UN Photo/Cia Pak.

Middle photo: Teodorin Obiang jr., son of the President. Photo: Facebook, derived from bellanaija.com.

Lower photo: Alfredo Okenve. Photo from Amnesty's website article Equatorial Guinea: Prominent human rights activist banned from receiving Franco-German prize.

This post has been written for the ASCL Africanist Blog. Would you like to stay updated on new blog posts? Subscribe here! Would you like to comment? Please do! The ASCL reserves the right to edit, shorten or reject submitted comments.

Comments

Add new comment

Thanks for this report: informative and useful!